For writers, this is a medium-level skill. For marketers, it’s as basic as bacon and eggs for breakfast…

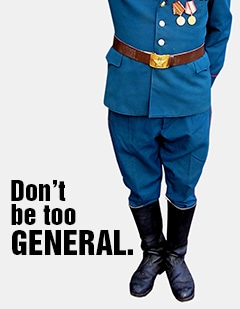

Specifics sell.

If you use generalities in your copy or make vague claims about your product, you’re leaving money on the table. The trouble is, even if you know the difference, you can inadvertently make broad promises that don’t inspire your customers to buy.

So let’s look at how you can identify those pesky generalities and transform them into specific details that will help your Web pages work harder and get better results.

Finding generalities that depress sales

From my experience, vague writing (whether it’s a sales page or a blog post) is always the result of laziness on the writer’s part. So the first place to look for uninspired writing is any page you had to write in a hurry.

What to look for:

Trying to say too much in too few words. When you don’t have room to say what you want to say, we tend to delete specifics rather than tightening our focus. So check your short pages for vague, wishy-washy writing.

Hyperbolic statements. When you don’t have specific numbers or data, but you want to impress people with your product’s popularity, you might settle for something like “best in the universe.” No details to back it up. Just a statement. The time for hype is over. Check your claims for these types of generalities.

“Pretend” proof. You just made a grand claim about your product but can’t find any research or proof to back you up. What do you do? Make a broad statement about “lots” of people liking your product. Look at all your proof statements for these pretenders.

What they might look like

Need some examples of what we’re talking about?

I pulled this paragraph from an old guest post submission:

Press release has always been the most useful resource to make the public and the media aware of the business’s products and services. Its popular networks like PRWeb or Business Wire have always helped many websites to generate great amount of authoritative back-links. Distributing a press release which is inserted with a related keyword choice in the prominent areas along with a newsworthy content always leads your company name to recognize as a credible brand. Don’t forget to include anchor-text specific links that highlight different terms. Besides that, a home page or sub page link in order to drive traffic to the main site or an internal page.

Bad writing aside, look at how vague it is. “Press releases has always been the most useful resource…” Who says? Why?

If you make a claim, you need to give an example or prove it.

For instance, here’s a paragraph I pulled from a study, Millennials as Brand Advocates, by SocialChorus.

Millennials are the most important consumer generation. Ever. They are the largest generation and are positioned to have more spending power than any other generation in history. But they don’t trust brands or advertising, which is creating big problems for marketers.

What if the writer had stopped after the first sentence? “The most important consumer generation” is a sweeping statement that raises questions in the reader’s mind.

I begin to think, “Oh yeah? Even more than the Baby Boomers?” and “Of all time? I’m not sure I believe that.”

Generalities tend to do that. They sound like important statements, but they don’t say anything at all. And they make people doubt the credibility of everything else you’ve said.

But in this example, that isn’t a problem. The writer immediately gives details that back up the statement and help me realize my questions will be answered if I keep reading:

- “Largest generation.” It’s a study, so I know numbers are coming. But if they weren’t, I’d want to see them here.

- “More spending power.” That jives with the “most important consumer generation” claim, so I can accept this for now. I begin to see here that “most important” relates to their financial power.

- “They don’t trust brands or advertising.” This, together with the previous statement, helps qualify the “most important” statement as well. It also piques my curiosity, which is going to keep me reading.

See what I mean?

If you make a general statement about size or value, you need to give specific details that help people believe your claims.

Let’s look at another example

This one comes from a Men’s Health sales page for the 28-Day Fat Torch Plan:

Researchers have found that starting around age 25, most people lose about 5 to 10 pounds of muscle each decade. Trouble is, muscle is a metabolically active tissue, which means it burns energy just to maintain itself. The less muscle mass you have, the less calories you burn. The result: Over time, you can slowly pack on stubborn belly fat.

Luckily, metabolic slowdown can be prevented with the 28-Day Fat-Torch Plan. While it would take 250,000 CRUNCHES TO BURN 1 POUND OF FAT, Durkin’s calorie-incinerating strength and power moves will build muscle and boost metabolism for as long as 39 hours after each workout. That means you’ll burn fat while sitting in the car, typing at your desk, and lying in bed sleeping.

Notice the details here.

- Age 25.

- Five to ten pounds of muscle each decade (not in general, but per 10 years).

- Then commentary that helps readers understand the implication of these details.

- Some impressive factoids: 250,000 crunches to burn 1 pound of fat.

- And the exercises in this program increase metabolism for 39 hours after each workout.

See how detailed it is?

What if the program had said: “As you get older, you put on weight. It’s a fact, and researchers have proven it.”

Would that work as well? No. You need the details to prove your claims and drive home your point.

Great marketing thrives on details

It doesn’t matter whether you’re publishing a blog post, a new home page, or a sales page, specific facts are what encourage clicks and sales.

Don’t settle for vague, wishy-washy copy. Never make a claim you don’t back up with detailed, precise facts.

Now you. Have you ever improved a piece of copy simply by making it more specific? Share your stories below.